The Armistice may have ended the fighting, but the war didn’t end for American soldiers like my grandfather–some 4 million in total. After their quick military training in the US and deployment overseas, they waited now to go home. (There were only a limited number of ships to transport them.) And they waited for assignments, for something to do. It was a time of uncertainty, a time of suffering from war wounds, and a time, for some, of despair.

Grandpa remained for months at the hospital complex near Mesves, in the Loire Valley. It was miserable that winter, raining all the time, he wrote. In photographs I’ve seen of the complex, where tens of thousands of soldiers received medical attention after the war, row after row of nearly identical barracks created a monotonous scene of uniform plainness (depressing to my eye). (1)

He tried to keep an upbeat tone in his letters, even as he admitted ongoing problems with his arm.

December 21, 1918 letter to Grandma.

After noting he hadn’t received mail in two months, he wrote,

My arm is plum healed up and don’t bother me at all only a little weak and I can’t straighten it plum out but I am sure if I were with you it would not bother me at all. Get me.

Did he think he would fully recover? In December, it seems he did.

“Our Division is up in the Rhine Valley as they are in the army of Occupation,” he wrote on December 14, a month into his recovery. “I would love to be with them, but you know I would rather come home you can bet.”

Neither of these were options, at least not at the time. Any hopes he held for a return to his company were dashed in early January. That’s when the doctors reviewed his condition and classified him as “C” class, which recommended “sedentary work” or work that didn’t include more than a five-mile march. (2)

Did he know, or want to suspect, that his injury would never fully heal, that it would limit his abilities the rest of his life?

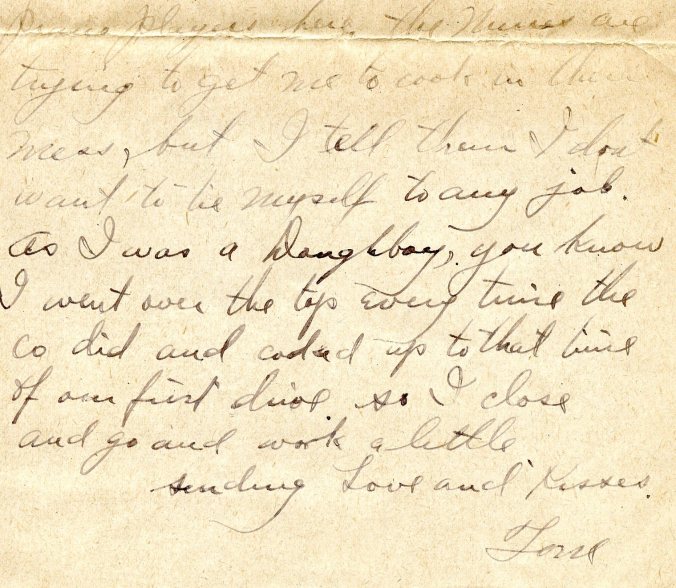

The one time I sense a note of despair in his letters, or maybe a bit of defiance, was here, in a letter written January 6, a few days after receiving his classification.

January 6, 1919 letter to Grandma.

After writing about piano players in the Red Cross “hut,” he continued,

The Nurses are trying to get me to cook in their mess, but I tell them I don’t want to tie myself to any job. As I was a Doughboy, you know I went over the top every time the co did and cooked up to that time of our first drive.

Wounded, he still identified as a soldier, still a member of Company C.

News from his buddies in Germany was scant. If he’d had better contact, Grandpa might have learned about the kind of despair some American troops faced there. I found this description in the History of the 89th Division, written by George English, himself a member of the division that served in Germany as part of the occupation. He recalls the days after the Armistice, when American forces began their march through the desolate “No Man’s Land” in France, on November 24, before entering Germany twelve days later, on December 5.

Should we mention our feelings on seeing green fields well kept–roofs and chimneys whole on the houses–fat cattle and well fed people in unharmed Germany–all after devastated France?

There was anger, he wrote, and also a note of melancholy.

The stately, spire-like poplars which line the French roads and give a characteristic tone to the landscape, were now supplanted by smaller, wide branching trees, whose gnarled and twisted limbs gave, in the winter season, a melancholy impression of suffering. (3)

My grandfather didn’t express his emotions, certainly not the way people do today. He witnessed suffering, and endured it, without complaint. That’s my memory of Grandpa. But what did he carry with him after seeing what he describes here, about halfway down? “When I look at so many one-arm, one leg’ed and one eye’d men I think I am sure lucky to only get a few scars on the arm.”

January 24, 1919 letter to Grandma.

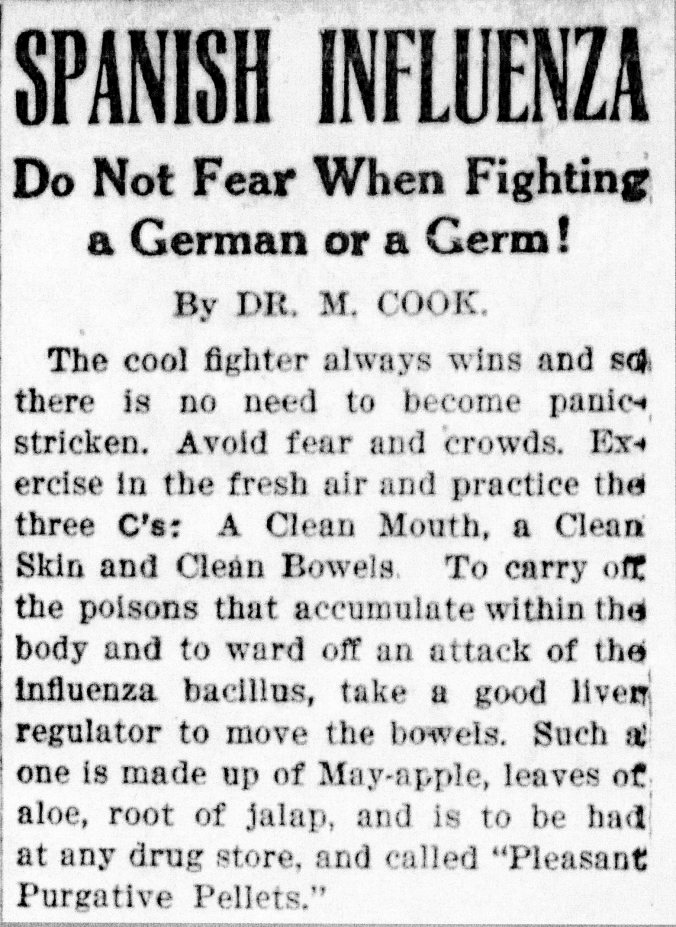

Suffering visited King City, Missouri, too, Grandpa learned in letters he received from home. “I was sure sorry to hear of so much sickness and so many deaths,” he wrote Grandma on January 3, 1919. This was a reference to the Spanish Influenza, the virulent type of flu that had become a worldwide pandemic, thanks in part to the movement of infected troops fighting in the war. The King City Chronicle ran notices of school and church closures, as well as obituaries of the victims. The paper also published advice columns from doctors, like this one recommending “pleasant purgative pellets” as a means of prevention.

King City Chronicle, 29 November 1918, p 3.

In that same letter, dated January 3, Grandpa continued, “I am hoping it will soon be stopped but as Mother said in her letter I guess everyone must have some trouble and it looks like it.”

His mother was right, of course. But I wonder if she or any one of that generation really comprehended the scale of suffering–from the war and the Spanish Influenza–and the steely presence each kept in the lives of its victims.

Some wounds never fully heal.

NOTES

(1) For photos and information (in French) on the hospital center: http://cnrs-garchy.overblog.com/le-camp-hopital-americain-de-mesves-bulcy

(2) From the research center at the National World War 1 Museum in Kansas City, I learned that this classification system likely was adopted from the British. Here’s the chart they sent me.

| A | Able to march, see to shoot, hear well and stand active service conditions. Subcategories: |

| Al | Fit for dispatching overseas, as regards physical and mental health, and training |

| A2 | As Al, except for training |

| A3 | Returned Expeditionary Force men, ready except for physical condition |

| A4 | Men under 19 who would be Al or A2 when aged 19 |

| B | Free from serious organic diseases, able to stand service on lines of communication in France, or in garrisons in the tropics. Subcategories: |

| Bl | Able to march 5 miles, see to shoot with glasses, and hear well |

| B2 | Able to walk 5 miles, see and hear sufficiently for ordinary purposes |

| B3 | Only suitable for sedentary work |

| C | Free from serious organic diseases, able to stand service in garrisons at home. Subcategories: |

| Cl | Able to march 5 miles, see to shoot with glasses, and hear well |

| C2 | Able to walk 5 miles, see and hear sufficiently for ordinary purposes |

| C3 | Only suitable for sedentary work |

| D | Unfit but could be fit within 6 months. Subcategories: |

| Dl | Regular RA,RE, infantry in Command Depots |

| D2 | Regular RA,RE, infantry in Regimental Depots |

| D3 | Men in any depot or unit awaiting treatment |

(3) English, George. History of the 89th Division. The War Society of the 89th Division, 1920, p. 263.

Susan, Very strong and affecting entry – it must have been so hard on him. I’m impressed with your series and hoping to meet you again before long – great job of creating this! I hope you continue and acquaint with your grandfather’s life after the war. Interestingly, my English grandfather, whom I never met (he emigrated to Boston about 1902) was sometimes accused of shirking, when he returned to England on visits later – and he felt great remorse on a trip to the battlefields sometime in the early 1920s. I’m thankful he survived, and I know he had no intention nor expectation of his move to America providing any such fate. Best to you, Susan! Sally

LikeLike

Thanks, Sally! The long reach of WW1 changed the lives of many Americans and their families (including recent immigrants). I’m always interested to hear those stories.

LikeLike

How debilitating emotionally to go from the terror of trench warfare to waiting around and having to the time to dwell on the horror you’ve just been through.

LikeLike

I agree.

LikeLike